Review – Tango Queer Buenos Aires

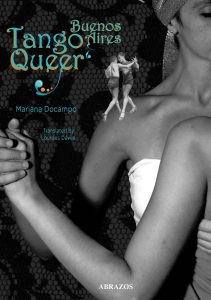

Tango Queer Buenos Aires

Tango Queer Buenos Aires

by Mariana Docampo

Translated by Lourdes Dávila

English version, published by Abrazos, 2020.

Review

by Ray Batchelor

The awareness of “being observed” is indivisible from tango and composes an image of tango that is simultaneously intimate and public…That is why tango queer can be thought of as a political weapon. It makes non-normative identities visible and, at the same time, opens new aesthetics of representation. (Mariana Docampo, Tango Queer Buenos Aires)

Like others whose command of Spanish is not yet good enough to allow me to read the 2018 Spanish original, I have waited in anticipation for this English version. I have now read it. Indeed, I have read it twice. This is, after all, the authentic voice of one of queer tango’s key players. This English language account helps close the linguistic fissure which runs between the Spanish- and English-speaking constituencies of queer tango. Both languages are spoken internationally with only a limited overlap. Queer tango is an international entity. Docampo’s book in either language will become a core text in the canon of queer tango literature.

Why? After all, as she herself acknowledges here, the term ‘Queer Tango’ or ‘Tango Queer’ – an English word combined with a Spanish one – is actually European in origin and, as Birthe Havmøller and I argued in our recently updated paper in ‘Queer Tango Histories’ (2020), it was first jointly coined in the late 1990s in Hamburg by German-speaking Ute Walter and Sabine Rohde. Similarly, in the late twentieth century, it was activists in Hamburg and not Buenos Aires who were the first to attempt to give their particular version of anti-heteronormative tango dancing a grounding in queer theory. Queer theory itself was neither a European nor a Hispanic product, but emerged out of Anglophone, principally north American academic circles. Queer tango has many roots, which is one of its strengths and gives it stability. But while others in Buenos Aires danced gay tango from the 1990s onwards – most notably, Augusto Balizano with Claudio Gonzalez, and Edgardo Fernández Sesma, all justly celebrated in their own rights – Docampo is universally credited with several pivotal innovations: with creating practices among women dancers in Buenos Aires, independently of developments in Hamburg, which became queer (rather than gay) tango in that city; with importing from Hamburg the conceptual underpinning of these practices; critically, also with importing the term “Queer Tango” (or “Tango Queer”) into Buenos Aires and so into Spanish; of opening in 2005 her famous milonga of the same name, according precisely to these inclusive, queer tango principles; and finally, with publishing in the same year her celebrated text ‘Tango Queer Manifesto’ setting out what, in her view, those principles are. A new, English translation of the ‘Manifesto’ is included in the book. Thereafter, colluding with Roxana Gargano and inviting Balizano to join them, since 2007 she has co-organised el Festival Internacional de Tango Queer de Buenos Aires. Ever since those events, Docampo has been in demand throughout the burgeoning international queer tango circuit (until the Covid-19 pandemic, that is) as a performer, a teacher, and occasionally as a guest speaker as, for example, at The Queer Tango Salon in London in 2017, where she presented us with some thought-provoking material – much of which has been incorporated into this book.

A word about the importance of the “Queer Tango” terminology. It matters what our dancing is called around the world. Docampo’s decision to use the term “Queer Tango”, or “Tango Queer”, was not uncontroversial. As is explained in this book, why, it was asked, should Argentinians to whom tango “belonged” adopt this foreign terminology? Docampo knew what she was doing. She draws careful distinctions between the manners in which queer tango was danced in Europe and in Buenos Aires early this century and, not surprisingly, favours the porteño iteration. However, advocating a term which conceptually aligned Buenos Aires queer tango dance practices with those in Europe, where the link with queer theory had first been forged, has ensured that in the years which have followed, the queer tango of Buenos Aires figures prominently and, arguably, pre-eminently in the evolving international landscape of queer tango.

While the later parts of her book set out much of the early history of queer tango, it may be that the earlier, less familiar autobiographical passages are those which non-Argentinians may find the most immediately engaging. Argentinians of her generation, for example, might take for granted her matter-of-fact descriptions of growing up in a respectable, Catholic, middle-class family with military connections, under military dictatorships of successively greater moral bankruptcy, savagery and repressiveness. Not so, those from other times or places. Docampo’s exploration of the “military” aspects of tango which she attributes to this national cultural context is engaging. As a historian of queer tango, perpetually frustrated at the lack of visual evidence of women dancing with one another when compared to that relating to men, I was much struck by her account of her maternal grandmother’s provincial upbringing. Her grandmother danced tango as a leader with other women – indeed she only danced with women, as she “belonged to a ‘good family’” and it would not have been respectable for her to dance with men. As a mature woman, her grandmother led Docampo and her sisters in tangos when they were young girls. One cannot help wondering how many more such informal, personal histories might eventually be drawn together. These, set alongside the insights offered by more formal studies such as Tango y género: identidades y roles sexuales en el tango argentino by Magali Saikin published in 2004, might help fill the void regarding the history of women dancing with each other Perhaps, in Spanish, this has already begun?

Similarly, those of us who practise queer tango elsewhere against – or rather in – the contexts of our own mainstream tango social practices will welcome Docampo’s first-hand accounts of her younger self going to milongas in late twentieth century Buenos Aires. Monica, her friend and accomplice in these early adventures, was older, straight, socially inferior, but more assertive. Monica used the cabeceo as an instrument of empowerment by which she chose her male partners, whereas Docampo, by contrast, modestly averted her gaze following a glance of invitation from a man and felt the cabeceo process an exercise in humiliation. Similarly, her atmospheric, first-hand accounts of – and eventual distaste for – the privileges accorded her as a follower by older male tango maestros on account, not of her dancing, but her good looks, youth and short skirts, make compelling reading.

An appreciation of the details of this personal journey are not only interesting in themselves and as social history, but also help explain Docampo’s particular set of beliefs about what objectives queer tango addresses, or ought to address. Indeed, one of the strengths of these accounts is Docampo’s mature, even-handed attitude towards rules and hierarchies. She despises the codigos and traditions of tango to the extent that they restrict freedoms or critical thought but, in a line of reasoning many tango dancers will recognise, respects them deeply to the extent that, paradoxically, they secure freedoms and make the dance possible at all. Not for her the crossing of the border from queer tango into Contact Improvisation, nor the suggestion that tango might, with advantage, be danced naked:

Tango bodies are not free. They are defined by culture and its marks (costumes, poses, movement codes). In tango, I need shoes [and] a proper wardrobe… There is nothing more absurd to me than dancing tango naked. The famous scene in the movie “Tanguito” from 1994 in which the protagonists dance naked and alone in a room is as brief as it would be in real life. Tango is culture.”

But respect for rules does not preclude radicalism, where the radical of queer tango come from the “queer”:

Queerness is the true subversive element in tango, because it shatters the pillars that hold up the traditional tango. Just queer visibility [alone] in tango turns the impostor body into a subversive body. And by subversion, I don’t mean destroying the dance but engaging with it, transforming it, updating it.

With occasional, contingent adjustments these, surely, are the foundational universals of queer tango.

As a woman who wanted to learn both roles, Docampo struggled in the straight prácticas, even when these were run by women. In part this was because, as her identity as a lesbian became clearer, so teachers and potential partners grew suspicious of her motives. These suspicions led to some uncomfortable encounters which might have put a lesser person off. But she persisted. Her assertion that “there were no role models at that point for what I wanted to do” is not strictly true in that there were, more or less, but they were in Europe and, in a world yet to be transformed by social media, remained unknown to her. Her persistence paid off.

Towards the end of this study, Docampo warns her (non-Argentinian?) readers “…tango is a delicate issue because it touches a nerve in many of us.” Queer tango’s linguistic fissure is only partially indicative of a wider, cultural one. As noted, almost from the first, queer tango, still more so even than tango itself, has had many roots and, accordingly, international dimensions. Queer tango is an international phenomenon. What then of the role of tango queer in Buenos Aires? Docampo writes:

If the contact with Germany gave a boost to queer tango in Buenos Aires, it was only in Buenos Aires under the radiant sun that suffused the bodies searching for new modes of expression, where one could find the power for tango queer to become a phenomenon that could radiate everywhere and could transform even the traditional tango circuit with its modernizing fire.

It is an attractive, poetic, superficially plausible assertion. I suspect in this, its unqualified form, many (myself included) will find it at odds with their senses of what has actually happened in queer tango in the last twenty years. Fortunately, Docampo herself gives a more nuanced account of the relationship between this primacy claimed for Buenos Aires and for Argentinians with regard to tango – and by implication, with regard to queer tango – as practised and taught by others from elsewhere in the world:

If we think of tango not as an abstraction of steps and technique, but rather as a dance that makes visible in every dancer’s body the variety of cultural and human elements that shape identity, it will cease to be merely the medium through which one learns to drag, hook or make a shape (barrida, gancho or boleo) and it becomes the means of transmission of a unique experience. In this sense, having travelled to milongas all over the world, I believe it is very valuable, from both human and artistic points of view, to look into the experiences of other countries. Expressed through bodies that [have] lived a history other than ours, built by another language and culture, these experiences can open new zones of perception in the dance and the relationship between the bodies, inspiring new spaces and transformations.

Elsewhere, Docampo mounts a spirited argument in favour of recognising the effects of a queer attitude towards the appreciation difference. There is an interesting debate still to be had about how judgements of the relative value of queer tango social dancing around the world are to be arrived at, about who is to make them, according to which criteria, and why.

A few grumbles: the editors at Abrazos, a publishing house I have had cause to admire, did Docampo a disservice by not insisting that the final English language draft was edited by someone with English as a first language and familiar with English tango terminology. Lourdes Dávila’s efficient, if occasionally inelegant translation is marred by terms which read as if they were generated by a tango-blind Google Translate: “a wide embrace” when what is meant is “open hold”; Helen La Vikinga, a much-loved figure in queer tango universally known by that name, becomes for no good reason “Helen The Viking”; worse, the term “new tango” is used instead of “Tango Nuevo”, with an obvious loss of precise meaning. Given the text’s Spanish origins, the decision to adhere to the Spanish printed language convention of putting a schedule of contents at the back of the book, rather than the front (which is the English convention), is perfectly defensible. Labelling that schedule an “Index” is not. An “index” in English is an alphabetical list of key words, terms, themes, places, names and so on, each followed by the page number or numbers where references to them are to be found. An index in that sense would have been welcome. Till then, we must wait patiently until the book becomes available digitally, so that we can mount such searches ourselves.

If I have a caveat, it is this: Tango Queer Buenos Aires is an informal mixture of memoir and polemic. Docampo has elected not to make it a conventionally-framed, more academic-style text, where a point of view supported by external evidence from identified sources is set out in a wider critical context and systematically contrasted with opposing points of view. There is in both languages a slender, but steadily growing body of literature relating to queer tango. By definition, an informal work does not need to be weighed down with the academic apparatus of annotation or a bibliography. Even so, with welcome exceptions and tantalising nods towards wider debates about both cultural and old-fashioned economic and political imperialism as well as power inequalities, there are few references, even casual and informal ones, to opinions or writings other than the author’s own. Paradoxically, while the views expressed here are set out with care, intelligence and authority, it could be argued they are made marginally weaker, not stronger, by choosing not to present them in a somewhat wider critical context.

That said, for all the reasons I have given and more, everyone should read Tango Queer Buenos Aires by Mariana Docampo!

Although steadily growing in number, there are still few authentic, articulate and intelligent voices emerging out of queer tango and still fewer by figures of Docampo‘s stature. The publication of Tango Queer Buenos Aires in English is a just cause for celebration.